Acting on Dreams: The State of Immigrant Rights, Conditions, and Advocacy in the U.S.

June 13 - August 30, 2015 | Franklin Street Works, Stamford, CT

Artists & Projects:

Andrea Bowers | CultureStrike & JustSeeds | Chitra Ganesh and Mariam Ghani | Ghana ThinkTank | Marisa Jahn (Studio REV-) in collaboration with National Domestic Workers Alliance and Caring Across Generations | Jenny Polak | QUEEROCRACY in collaboration with Carlos Motta | Favianna Rodriguez

Overview:

Immigrants now comprise approximately 13 percent of the total U.S. population (41.3 million), of which over a fourth are undocumented (11.4 million) and close to a fifth live in poverty. Many have called for an overhaul of the immigration system, seeing it as a necessary and crucial step in the development of a more humane and just American society. Yet many others still fail to acknowledge and empathize with immigrant hardships and the ways in which our culture is implicated. They overlook the lasting legacy of U.S. interventions in Latin America and the Middle East, the racial discrimination embedded in American society, the politics of immigration reform, and more than anything – the undeniable economic motivations keeping immigrants in the country, and out of the legal labor market. Acting on Dreams presents many of these struggles, but also the inspiring work of community activists and artists who attempt to fill the enormous gaps in immigration services and knowledge.

With a recent surge in border crossings on the one hand, and stalled legislation in Congress and increased deportations on the other—the work of individuals and grassroots organizations to raise awareness and ease immigrant conditions has become increasingly essential. Rather than wait for politicians to end the existing practices of exclusion and persecution, initiatives such as those included in this exhibition prompt each of us to envision a new system that genuinely supports, acknowledges and serves migrants and their communities. The artists use their creative skills to further compassionate and respectful policies, and strive to communicate the immigrant experience in the United States—the frequent sense of isolation and uncertainty, but also courageousness, pride, and anticipation.

*This exhibition is accompanied by a booklet with an essay by Yaelle Amir. Download a copy here (PDF).

Curatorial Statement:

In the mid-2000s, a group of self-appointed border guards – so-called "Minutemen" – declared their mission to protect the southern borders of the United States from migrants entering the country without papers. Their stated goal: to stop the "illegal invasion of America." Armed with a vigilante attitude, they often described their actions using language fit to portray a hunting expedition, rather than a volunteer-run patrol searching for fellow human beings.[1] While the Minuteman Project has subsided for the time being, its very existence raises broad questions. How did the U.S. – a country of immigrants – arrive at a state of extreme nationalism, sanctioned exclusionism, and rigid definitions of legal status and ideologies? How and why did travel become an entitlement belonging only to those in power? What does the existence of a group so fervent about denying individuals entry into the U.S. – the avowed "land of opportunity" – and widespread anti-immigrant rhetoric, tell us about the state of human rights in our country?

Immigrants now comprise approximately 13 percent of the total U.S. population (41.3 million), of which over a fourth are undocumented (11.4 million) and close to a fifth live in poverty.[2] Many people claim that rather than seeking refuge and employment in the U.S., migrants should stay in their own countries and change the systems that are oppressing their quality of life and pushing them out. Those who say this, however, have a misguided view of the history of migration to this country, and overlook the lasting legacy of U.S. interventions in Latin America and the Middle East, the racial discrimination embedded in American society, the politics of immigration reform, and more than anything – the undeniable economic motivations keeping immigrants in the country, and out of the legal labor market.

The exhibition Acting on Dreams is informed by the policies that have shaped the U.S. immigration system and resulted in such strong convictions and emotional reactions. While there are many more factors to take into account beyond the scope of this essay, the following overview attempts to provide information essential to the issues addressed by the seven projects featured in the show, and to which the artists hope to raise awareness and offer solutions. Hopefully, by learning about the evolution and some of the fundamental aspects of immigrant rights and conditions, viewers and readers will feel better equipped to further engage with this intricate and contentious cultural matter.

Early Migration and Labor Policies

In trying to understand the reasons for the presence of 11.4 million unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. (of which over 6 million are Mexican)[3], we must first examine the country's border and migration policies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Prior to 1890, there were virtually open borders between the U.S. and its neighbouring countries, there was no system to enforce or control immigration, and therefore an "illegal" status did not exist. The first deportation law was passed in 1891, allowing for the removal of an immigrant who became a "public charge" within the first year of arrival. After one year, however, the individual can no longer be deported.[4] Entering the country without an inspection first became a violation in 1907. The 1924 Immigration Act introduced the "quota system" by which each European country was permitted a certain number of immigrants per year. Notably, this did not apply to migrants from south of the U.S. border. This law also deemed entry without inspection illegal and no longer offered a statue of limitations on deportability.

This short timeline reveals different attitudes based on the race and origin of immigrants. As Aviva Chomsky articulates, in the nineteenth century "(i)mmigrants were the Europeans who came to Ellis Island; workers were the Mexicans and Chinese who built the railroads and planted the food that sustained white settlement in the newly conquered west of the country."[5] Up until the second half of the twentieth century, Mexicans were not viewed as prospective immigrants, but rather as temporary, seasonal workers who entered the U.S. to answer labor demands in the industrial and agricultural fields, and returned home at the end of the season. They serviced the dual labor market—a by-product of the global industrial economy where some workers benefitted from it by becoming upwardly mobile and others were kept at the bottom with legal and social constraints.[6]

To respond to a rise in demand for agricultural laborers following the Great Depression and the shortage resulting from World War II, the government formed a guest worker program in 1942. Both the U.S. and Mexican governments administered the Bracero Program, recruiting 4.8 million seasonal migrant workers between 1942 and 1964.[7] In this arrangement, the workers' families were not permitted to join them and the U.S. government kept 10% of their paycheck until the end of the season to ensure that they return home.[8] This was the first time in which the temporary and exploitative attitude towards Mexican labor was written into law.[9]

Mexican migrants became essential to the success of the U.S. economy – they provided inexpensive, exploitable, temporary labor and were not perceived as potential citizens.[10] In failing to adequately address migrant workers, these early immigration policies bifurcated the working class by race and nationality.[11] The U.S. thus permitted the establishment of an international working class within its borders as a necessary step in the accumulation of capital. Illegal immigration has always been an indicator of the health of the U.S. economy—the demand for low-skilled migrant labor is high when the economy is growing, and tapers off when there is a downturn, as had happened most recently during the 2008 recession.[12] This is a crucial point in understanding how the recurring phases of anti-immigrant sentiment and policy tracks the expansion and contraction cycles of the U.S. (and world) economy, as well as the current struggle to regularize the status of undocumented workers. Not only has the U.S. government created the reliance on these workers—the prosperous American economy would not, and cannot, exist without their labor.

Introducing the Concept of Illegality

While other countries legalized their guest workers when discontinuing initiatives similar to the Bracero Program, the U.S. outlawed them overnight with the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965. This law distributed equal quotas to all countries, resulting in the classification of Mexicans as immigrants for the first time. This ended the Bracero Program, yet the need for these workers did not vanish along with their legal status. 1965 was essentially the start of "illegality" as we know it today.

This new state of affairs was informed primarily by the contemporary gains of the Civil Rights Movement, by which overt race-based restrictions became increasingly socially unacceptable. Citizenship status, however, did not threaten the air of social progress, and thus became the tool with which the dual labor market system maintained its viability. Workers were now cheap due to their lack of papers, not (supposedly) the color of their skin. This exploitable labor force developed and mushroomed to the point where in the mid-1980s there were between three and five million undocumented immigrants in the country.[13] As a result, Congress passed the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), addressing the issue of unauthorized migration for the first time. This law legalized the status of approximately 2.7 million immigrants, implemented new border control measures, and set penalties for employers hiring unauthorized workers.[14] However, the IRCA was ultimately deemed a failure for various reasons, including its arbitrary exclusion of all immigrants who had been in the country for less than five years, its poor funding for border enforcement, and its diluted sanctions against employers.[15]

In the long run, these laws had little effect in that they were unable to mitigate the number of unauthorized border entries. They offered few solutions for regularizing the status of workers who were fundamental to keeping the American economy going, especially during the boom of the 1990s. Lawmakers continued to cater to the desires of business owners, who strived to guarantee a permanent underclass of undocumented workers that can provide cheap, exploitable labor, while simultaneously succumbing to increasingly militant calls by nativist groups to secure the country's southern border.[16]

Racializing and Criminalizing Immigrants

While the southern border became the focus of anti-immigration advocates, the country's northern border remained virtually unpoliced. This fact points to the highly racialized nature of the campaigns lodged against the undocumented, and the veiled racial motivations guiding those determining who is permitted to become an official member of this nation. This approach has resulted in a call for heavy policing of the southern U.S. border, and the criminalization and prosecution of primarily Hispanic immigrants and their children.

In 1994, the then-Immigration and Naturalization Service agency (INS) introduced the first official border control program along the U.S.-Mexico border, which applied strategies of "prevention through deterrence." The agency built roads, installed barriers and surveillance equipment, and deployed Border Patrol agents to apprehend unauthorized entrants.[17] This program was expanded in 1996 by broadening the scope of crimes deemed deportable and also applying them retroactively, increasing the number of Border Patrol agents, and eliminating access to most public-assistance benefits for both undocumented and permanent residents.[18] This coincided, ironically, with the introduction of the Independent Taxpayer ID Numbers (ITINs), which enabled immigrants without papers to pay taxes, yet never collect any Social Security or health benefits.[19]

The attacks of September 11, 2001 had an unprecedented effect on attitudes towards immigrants, whether recognized or undocumented. It is at this point that immigration concerns became officially an issue of national security. First, the INS, which had been part of the Department of Justice, was dissolved and reconfigured under the authority of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). As part of these changes, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was formed to enforce immigration laws including detention and deportation. This new era also established the USA Patriot Act (2001), which gave free reign to law enforcement agencies to monitor, search, detain and remove any foreign nationals with little oversight. In 2005, the REAL ID Act banned states from issuing driver's licenses to unauthorized individuals, thus limiting their movement even further.[20] These new laws had an alienating and divisive effect on the American population, heightening the atmosphere of fear, suspicion and bitterness towards immigrants that had already been percolating beneath the surface prior to 9/11. The Secure Communities program of 2008 has further criminalized immigrants by establishing a data-sharing system between local law enforcement agencies and ICE, where fingerprints taken at an arrest are cross-referenced against federal immigration records to determine if the individual should be detained.[21]

Concurrently, this new era ushered in a massive expansion of the private prison industry. In 2005 the government introduced Operation Streamline by which unauthorized migrants attempting to cross the border are served with criminal charges.[22] They are detained and tried at the government's expense, instead of simply returned to Mexico.[23] Individuals stay in detention facilities for months or even years, awaiting their appearance before an immigration judge to determine their fate. In comparison to the criminal justice system – an already deeply problematic structure – immigration detainees fall into a legal loophole resulting in unregulated conditions, including medical and mental care, access to telephones and free legal assistance.[24]

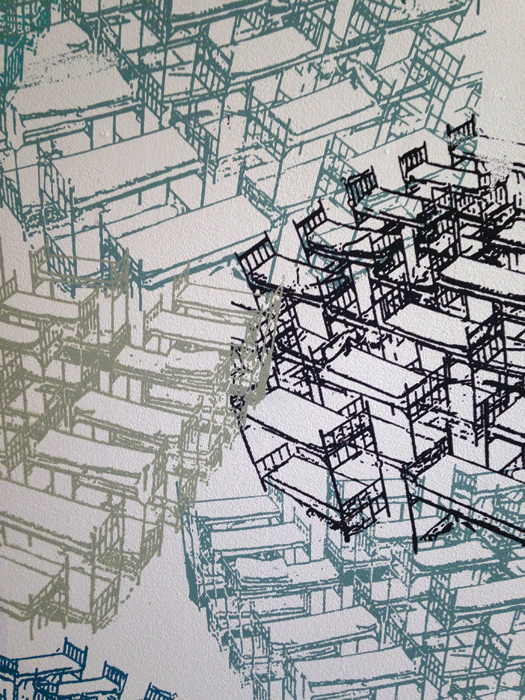

As a result of continuous enforcement efforts, the detention and deportation system has grown exponentially in recent years, reaching a peak in 2013 with well over 400,000 people deported.[25] ICE's budget grew from $864 million in 2005 to $2 billion in 2012.[26] This increase in "demand" has resulted in a need for more facilities, which the government has contracted out to private prison companies. Half of all detainees are currently held in private penal facilities, compared to a fourth about a decade ago.[27] Since 2005, the federal government has spent $5.5 billion on private contracts to prison companies—this embodies a self-perpetuating system of criminalization and incarceration whereby immigration policies create demand for private detention facilities.[28] The prison companies, on their part, are creating a market for their product by lobbying for (and receiving) stricter immigration policies.[29]

While considering all the vested interests described above, it is crucial to remember that border militarization – the walls, technology, facilities, criminalization policies, etc. – has failed in stymieing migrant flow, for it overlooks the systemic reasons for migration that make the high risk worth taking. This includes the war-torn regions where the U.S. is implicated, the vicious drug wars in Mexico, trade deals like NAFTA, and the incentives provided by American employers.

A New Push for Immigration Reform

Hand-in-hand with the increased border militarization policies of the Obama administration –which has detained and deported far more immigrants than any prior administration – it has firmly pushed to overhaul the broken U.S. immigration system. In 2012, Obama announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), providing work authorization and protection from deportation for two years for unauthorized immigrant youth under the age of 31, who have resided in the U.S. continuously since June 2007.[30] It was estimated that approximately 2.1 million individuals were eligible under DACA (about 10 percent of the total undocumented population), with 727,164 requests accepted as of December 2014.[31] After several failed proposals set forth by the Obama administration, including the DREAM Act (2012) and bill S. 744 (2013), Obama issued an executive order in November 2014 that would affect approximately 4 million immigrants without papers. Under this policy, the undocumented parents of U.S. citizens and permanent residents who have resided in the country for at least five years would have legal reprieve from deportation and will be able to obtain work permits. The action would also expand DACA to include individuals older than 30. As of May 2015, this order has yet to be enacted as it is being legally contested in over half of the states. While Obama's plan offers some solutions, it still will not cover more than half of the undocumented immigrants residing within U.S. borders.[32] Furthermore, it coincides with directives for increased deportations and policing along the border, even though they have been proven to be ineffective, dangerous, and culturally divisive.

Acting on Dreams

This overview of the history and current state of immigrant rights and conditions in the U.S. brings some focus to the ongoing precarity of 11.4 million unauthorized immigrants, and the millions more permanent residents and recently-naturalized immigrants. Despite the numerous roadblocks described hitherto, many in the U.S. have called for an overhaul of the immigration system, seeing it as a necessary and crucial step in the development of a more humane and just American society. Yet many others still fail to acknowledge immigrant hardships or to empathize with their conditions, prompting forward-thinking individuals, such as community activists and artists like those in Acting on Dreams, to attempt to fill the enormous gaps in immigration services and knowledge.

With a recent surge in border crossings on the one hand, and stalled legislation in Congress and increased deportations on the other—the work of community and grassroots groups to raise awareness and ease immigrant living conditions has become more essential. This exhibition is by no means a comprehensive account of the remarkable work being done by individuals in support of immigrant communities. The works included in this exhibition chronicle several efforts of immigrants and their advocates, while drawing connections between various communities and concerns within this highly complex issue. The artists apply their creative skills to further compassionate and respectful policies, and strive to communicate the immigrant experience in the U.S.—the frequent sense of isolation and uncertainty, but also courageousness, pride, and anticipation.

In her video Sanctuary, Andrea Bowers tells the story of Elvira Arellano, an undocumented immigrant who entered into sanctuary on August 15, 2006, at the Adalberto United Methodist Church in Chicago in order to avoid the prospect of deportation and separation from her 8-year old son, a U.S. citizen. Arellano was ultimately deported a year into her stay at the church, and continues to organize from Mexico. The work attaches a face to the ruthless federal deportation policies that often go overlooked and reinforced in the discussions of policy reform.

The Index of the Disappeared is an evolving multidisciplinary, physical archive and platform for public dialogue that embodies a haunting chapter in U.S. history. Artists Chitra Ganesh and Mariam Ghani have worked to compile an archive around post-9/11 disappearances to highlight the uncertainty many immigrants have experienced as a result of the geopolitical and policy shifts in the U.S. since 2001. Through official documents, secondary literature, and personal narratives, Index traces the ways in which censorship and data blackouts have enabled unprecedented disappearances, deportations, renditions, and detentions in the lives of immigrant, "other," and dissenting communities in the U.S. A portion of the archive is included in the exhibition with a purpose of confronting audiences with the human costs of public policies, connecting domestic and foreign policies and policing, and challenging viewers to reevaluate the abstractions of political rhetoric in individual terms.

In ThinkTank at the Border, Ghana ThinkTank has developed a multi-year project in an effort to investigate the seemingly un-crossable divide between "opposing" sides of immigration-related issues, collecting problems from citizen border-patrols like the Minutemen, and bringing them to recently deported or undocumented immigrants to solve. They collect these problems through focus groups, street interviews, and postcards, and present the immigrants' solutions back to the Minuteman-like groups, working to find ways to have them implemented. The exhibition presents an iteration of the project, Border Cart – a mobile cart designed to fold into the back of a Tijuana Taxi, and then unfold at the border to provide shade, a seat, and a public think tank process to people crossing the U.S. – Mexico Border. Their border project is an outgrowth of a longer term project initiated in 2006 to "Develop the First World" by sending problems from the so-called "first" world to think tanks in Cuba, Ghana, Iran, Mexico, El Salvador, and the U.S. prison system to be solved.

In an ongoing body of work entitled "CareForce," artist Marisa Morán Jahn (Studio REV-) in collaboration with the National Domestic Workers Alliance and Caring Across Generations uses an artistic framework to develop tools that assist domestic workers in learning their rights and advocating for their socio-economic justice. Bridging public art, law, tech, and design, their projects have taken on various forms. From a mobile design lab and sound studio, to dance and movement, to an informative app accessible by any kind of phone—they offer crucial support to those who take care of our children, family, and homes.

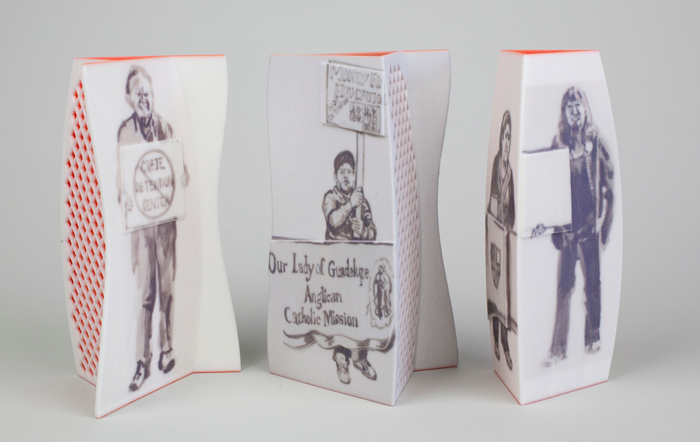

Jenny Polak has worked with residents and immigrant activists in Illinois and Indiana to advance recent struggles in blocking the construction of for-profit immigrant detention centers in their midst. Polak maintains an ongoing relationship with key figures in these communities—collaboratively developing imagery to create custom domestic objects that raise awareness to the effects of detention centers on jailed immigrants and on their surrounding communities. The photographs, drawings, and figurines that comprise (n)IMBY also assist the campaigners in documenting their achievements so that others can refer to them as a model.

On Columbus Day in 2011, Queerocracy in collaboration with the artist Carlos Motta organized the distribution and collective public reading of excerpts from A Timeline of Queer Immigration – an exhaustive list of significant events in the global queer and immigrant movements. The intervention took place at Columbus Circle, the site commemorating the individual who marked the official start of immigration to Northern America. The timeline begins with Columbus' arrival in 1492 and continues with dozens of seminal events that highlight the parallel struggles of immigrants and queer individuals to be recognized as equal citizens.

Artist Favianna Rodriguez co-founded CultureStrike, a grassroots arts organization that engages cultural producers in migrant rights. Her work stems from the belief that art is necessary in promoting awareness of the disastrous effects of U.S. immigration policies, and in countering the often-negative perception of immigrants. As part of these efforts, Rodriguez initiated the campaign Migration is Beautiful featuring the now-iconic monarch butterfly symbol. The exhibition includes a coloring station by Rodriguez that provides advocates with on-site tools to construct their own butterfly wings in a public display of support for immigrant rights, as well as Migration Now!, a comprehensive print portfolio by CultureStrike and JustSeeds.

Conclusion

Rather than wait for politicians to end the practices of persecution and deportation, the initiatives such as those included in this exhibition prompt each of us to envision a new system that genuinely supports, acknowledges and serves migrants and their communities. For this to happen, it is first essential that those of us whose legal rights are not in question acknowledge the ways in which we, as a society, are complicit in the current status quo, and are benefitting greatly from the ongoing flow of undocumented immigrants. It is time that we take responsibility for how U.S. policies both at home and abroad have shaped the current state of immigration—specifically demanding of ourselves and our elected leaders that solutions be found for ensuing systemic problems in countries like Colombia, Iraq and Mexico, while instituting more welcoming policies to individuals from regions affected by U.S. imperialist actions. Furthermore, we must understand the discriminating nature of our laws, where white and wealthy Europeans have traditionally been welcome, while poor individuals from the southern hemisphere and eastern countries have faced severe restrictions. We also need to recognize borders for what they are – arbitrary demarcations of power servicing the privileged at the expense of the disadvantaged. If we begin to view the undocumented status as a tool used by the capitalist system to ensure that there is always an invisible, exploited underclass—perhaps it would be easier to mobilize fellow members of the working class around rejecting it.

Missing from this essay are many additional factors that play into the U.S.'s immigration crisis, including the drug cartels that instill fear in the lives of individuals living south of the border, the raging violence in Central America, and many local policies across the world that make those places uninhabitable for so many. Since its founding, the U.S. has defined itself as a land of opportunity, one which welcomes individuals of all classes and origin. It is even spelled out on the historic gateway to the country, the Statue of Liberty: "Give me your tired, your poor/ Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free / The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. / Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me / I lift my lamp beside the golden door!" While it would be naïve to presume that this vision was entirely possible then, or now—it begs a reminder that these were our stated national values at some point in time, and we have since moved far away from them. The strong call heard among immigrant advocates that no human being is illegal, is one that expresses basic humanity essential to the values of every society. It is a summons for all of us to demand of our government to open U.S. borders and cease its persecution of those who we initially invited to build and enrich our culture, and who are today an invaluable part of American society.

- Yaelle Amir, May 2015

_____

Endnotes: [1] Michael Scherer, "Scrimmage on the Border," Mother Jones, July/August 2005 Issue. Read more about the Minuteman Project on their website: http://minutemanproject.com [2] Jie Zong and Jeanne Batalova, "Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States," Migration Policy Institute, February 26, 2015 [3] This statistic is from 2013: Zong and Batalova. [4] In 1903, this period was extended to two years, and in 1917 to five years. [5] Aviva Chomsky, Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal (Boston: Beacon Press, 2014), 10. [6] Chomsky, 9. [7] Chomsky, 57. [8] Justin Akers Chacón and Mike Davis, No One is Illegal (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2006), 143. [9] This also had an enormous impact on the Mexican economy in the 1950s, when these workers brought home $30 million in remittances – the third largest source of income in the country. Akers Chacón and Davis, 145. [10] Chomsky, 182. [11] Akers Chacón and Davis, 174-5. [12] Faye Hipsman and Doris Meissner, "Immigration in the United States: New Economic, Social, Political Landscapes with Legislative Reform on the Horizon," Migration Policy Institute, April 16, 2013 [13] Hipsman and Meissner. [14] Unauthorized immigrants living in the U.S. consistently since 1982 became eligible for temporary legal status, and could apply for a green card after 18 months. D'vera Cohn, "How the 1986 immigration law compares with Obama's program," Pew Research Center, December 9, 2014 [15] To appease the business community, Congress watered down the employer sanctions to the point of ineffectiveness. The IRCA also created a whole new industry of falsifying documents to prove continuous residence in the country since 1982. The 1990 Immigration Act (IMMACT) attempted to close some of the gaps of the 1986 Act by offering temporary legal status to immigrants from countries afflicted by war or natural disaster. Brad Plumer, "Congress tried to fix immigration back in 1986. Why did it fail?," The Washington Post, January 30, 2013 [16] Members of nativist groups have blamed immigrants for job losses and the demise of small businesses, rather than looking to the employers outsourcing these jobs and the rise of major corporations. For more on nativist claims, see Chapter 28 in Akers Chacón and Davis. [17] Doris Meissner, Donald M. Kerwin, Muzaffar Chishti, and Claire Bergeron, Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery (Washington, D.C.: Migration Policy Institute, 2013), 24. [18] Migration Policy Institute, Major U.S. Immigration Laws, 1790 – Present (Washington, D.C.: Migration Policy Institute, 2013), 5-6. [19] An estimated 75 percent of undocumented immigrants pay into Social Security and Medicare through payroll deductions. Akers Chacón and Davis, 165. [20] Hipsman and Meissner. [21] Hipsman and Meissner. [22] Entering the country illegally is considered a crime punishable by up to six months in prison; A repeat entry into the country after being deported is a felony subject to up to two years in prison; Being in the U.S. without papers is a civil violation that is resolved by voluntary or forced removal. Chomsky, 98. [23] According to data from 2012, the cost of detaining an immigrant is $164 per person/per day. Detention Watch Network, About the U.S. Detention and Deportation System Accessed 5 May 2015. [24] American Civil Liberties Union, Immigration Detention Conditions Accessed 5 May 2015. [25] Zong and Batalova. "From 1996 to 2006, 65 percent of immigrants who were detained and deported were detained after being arrested for non-violent crimes. Between 2009 and 2011, over half of all immigrant detainees had no criminal records. Of those with any criminal history, nearly 20 percent were merely for traffic offenses." National Immigration Forum, The Math of Immigration Detention, August 22, 2013 [26] Chomsky, 62. [27] Chris Kirkham, "Private Prisons Profit From Immigration Crackdown, Federal And Local Law Enforcement Partnerships," Huffington Post, June 7, 2013 [28] Chomsky, 104.Chomsky, 104. [29] "Corrections Corporation of America (CCA) is the largest ICE detention contractor, operating a total of fifteen ICE-contracted facilities with a total of 5,800 beds. GEO Group, Inc. (GEO), the second largest ICE contractor, operates seven facilities with a total of 7,183 beds. In FY2012 CCA and GEO reported annual revenues of $1.8 billion and $1.5 billion respectively": The Math of Immigration Detention. See also Chomsky, 108-112 for details on the ways in which private prison corporations have lobbied and advocated for strict immigration policies that require the detention of unauthorized migrants./ [30] In 2014, Obama announced the expansion of DACA to youth that arrived before June 2010, though it is currently being contested in the courts and therefore not yet enacted. [31] "Data Set: Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals," U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, February 12, 2015. Accessed 5 May, 2015. [32] Migration Policy Staff, "As Many as 3.7 Million Unauthorized Immigrants Could Get Relief from Deportation under Anticipated New Deferred Action Program," Migration Policy Institute, November 19, 2014

Press:

Danilo Machado, Social Justice in the Studio and in the Street: Art and Activism at Franklin Street Works, 6 July, 2015