at last, I see you

June 25 - July 23, 2022 | Melanie Flood Projects, Portland, OR

Artist:

Ricardo Nagaoka

Overview:

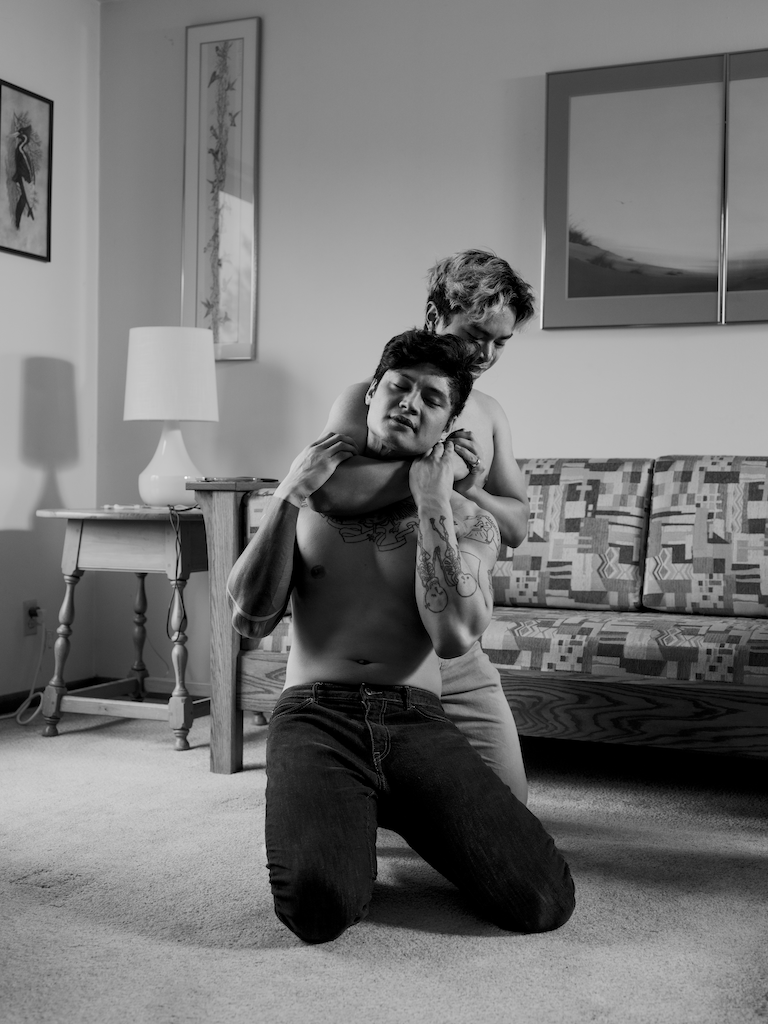

Ricardo Nagaoka created the photographs of at last, I see you to complicate the ideals set for masculinity by the U.S.’s predominantly white, heteronormative culture. By capturing intimate portraits of his male and non-binary friends, family members, and new acquaintances in their own homes, Nagaoka distills a tense undercurrent that serves to counter society’s preconceptions of maleness.

This solo exhibition of Nagaoka'’s work was curated by Yaelle S. Amir for Melanie Flood Projects in Portland, OR.

curatorial statement:

Stemming from his own Asian male identity, Ricardo Nagaoka created the photographs of at last, I see you to complicate the ideals set for masculinity by the U.S.’s predominantly white, heteronormative culture. By capturing intimate portraits of his male and non-binary friends, family members, and new acquaintances in their own homes, Nagaoka distills a tense undercurrent that serves to counter society’s preconceptions of maleness. Encouraged to take command of their representation within their personal spaces, his subjects appear in various vulnerable states—reclining in the nude in their bedrooms, flexing muscles partially veiled by feminine clothing, quietly struggling and/or embracing. The domestic space denotes here the environment where people can be most themselves, where they can shed the layers of social expectations.

To fully understand this body of work, we must recognize the unique history of marginalization and racist representations of Asian males since the early nineteenth century in the U.S. The first significant influx of immigrants from Asia began in the mid-1800s, with laborers arriving from China, Japan, the Philippines, Korea, and India to work in railroad construction, on plantations, and as part of the California Gold Rush, among other jobs. Soon after, the U.S. government began passing restrictive laws targeting this population. It started with the Page Act in 1875 which was meant to limit population growth and maximize efficiency amongst Asian laborers by prohibiting the immigration of their wives and children. Anti-miscegenation laws were also introduced to guarantee that Asian men did not marry White women. Additional laws followed, barring immigration from specific Asian countries including the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Gentleman’s Agreement in 1907 (Japan), and the Barred Zone Act in 1917 (South Asia and Polynesia). These restrictions arose from the impact European migrants thought Asian immigrants might have on their employment opportunities, as well as from their conventional perception of gender roles. The latter originated from the Asian laborers’ willingness to launder clothes and prep food—tasks that were traditionally seen as women’s work in the Western tradition.

This institutional persecution and rise of xenophobic sentiments towards Asian immigrants were further reinforced by a racist, global cultural campaign that saw the rise of the image of the “Yellow Peril.” This imagery appeared in media from the mid to late 1900s and depicted Eastern and South Asians as belligerent caricatures who pose an existential threat to the Western world. The specific origin of the subjects in this imagery would shift over time in line with global politics, with widespread iterations seen as recently as the Trump administration’s COVID-related vitriol against China.

Also widespread from this era were depictions of Asian men as effeminate or asexual. This typecast originated in the aforementioned challenge to traditional gender roles, as well as the White man’s campaign to emasculate Asian men who were perceived as competition for the hearts of White women. Hence, the stereotypical depictions of Asian males as both aggressive and as weak were borne from the same place where many bigoted perceptions often take form – the persistent insecurities of White men.[1]

These racist depictions have endured in print, on stages, and on screens for well over a century, with our culture becoming generally indifferent to them. It is these stereotypes that Nagaoka is challenging in his portraits, where he emphasizes the nuances of his subjects’ gender identity by collapsing various attributes into single images. As viewers, we are called to sit within this subtle space, as Nagaoka highlights the contradictions inherent to his subjects. With slight adjustments to their position, environment, and light he confuses society’s deep-rooted, hegemonic perception of masculinity. The individuals’ strength, tenderness, sexuality, vulnerability, aggression, and kinship are all present—diffusing mythologies, tropes, and societal misconceptions. In celebrating these tensions within each portrait, Nagaoka thus works to reclaim the popular imagery of Asian masculinity. In so doing, he breaks down generations of patriarchal and racist foundations, and simply asks the question: “how might men become whole again?”

Yaelle S. Amir, June 2022

—

[1] This succinct historical overview was gleaned from the following source: Shek, Yen Ling. "Asian American Masculinity: A Review of the Literature." The Journal of Men's Studies 14.3 (2007): 379-91.

About the Artist:

Ricardo Nagaoka is an artist born and raised in Paraguay and a grandson of Japanese immigrants. He immigrated to Canada with his family during his teenage years, and eventually landed in the U.S to study at the Rhode Island School of Design (BFA in Photography). He currently lives and works in Portland, OR. Growing up as a descendant of Japanese heritage in a culturally homogeneous country, he was an outsider in his own homeland. His surroundings insisted on him to define his own agency, challenging his cultural and familial identities from a young age. Ricardo’s work seeks to explore our constructs and ideas of home, selfhood, and masculinity. He finds an urgency in questioning the tendency to frame identities through their immediate surfaces, where the complexity of our conditions is often pushed aside for the status quo.

This exhibition was generously supported by a Make | Learn | Build grant from the Regional Arts and Culture Council, and a Career Opportunity Grant from Oregon Arts Commission & The Ford Family Foundation.

Press:

Luiza Lukova, “Ricardo Nagaoka at Melanie Flood Projects,” Oregon ArtsWatch, July 8, 2022